On Travels with Charley

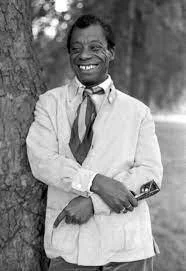

I like forming theories about literature - particularly theories based on zero evidence. It must be a hangover of studying English at university and being forced to provide evidence for all my reckless assertions - now I treat myself to the occasional assertion, the more reckless the better. My current favourite is this: just as you are either a cat person or a dog person, United or City, Italian or French food: you are either a Hemingway person or a Steinbeck person.

Like I said, this is based on nothing other than a hunch. Lots of people seem to like Hemingway, and I expect they have their reasons, but I refuse to entertain them. Steinbeck was a better novelist, a better pet owner, and a nicer man. Consider Hemingway’s famous ballscratching machismo, as refracted through his obsession with fly-fishing. And then consider this, from Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley:

‘I have no desire to latch onto a monster symbol of fate and prove my manhood in titanic piscine war. But sometimes I do like a couple of cooperative fish of frying size.’

Steinbeck’s Travels with Charley is, according to historians, not factual enough to be considered nonfiction. It seems that Steinbeck did go on a road trip to rediscover America, and he did take his poodle, Charley, as his companion. What he doesn’t mention in the book is that this trip was undertaken in the knowledge that he was dying, and this was his final opportunity to survey the country that had been the subject and the muse of his life’s work. And so he does, with exquisite, loving detail, in a book that became - over the course of a lazy afternoon in a hammock - one of my all-time favourites.

Steinbeck’s journey does not particularly concern itself with the grand, for he feels that the more ostentatious avatars of American life aren’t representative:

Perhaps this is because they enclose the unique, the spectacular, the astounding - the greatest waterfall, the deepest canyon, the highest cliff... for it is my opinion that we enclose and celebrate the freaks of our nation and of our civilisation. Yellowstone National Park is no more representative of America than is Disneyland.

He is much more interested in the everyday, and his curiosity towards his fellow Americans is equal-opportunities in its insatiability. Of a small-town diner waitress, he writes: She wasn’t happy, but then she wasn’t unhappy. She wasn’t anything. But I don’t believe anyone is a nothing. There has to be something inside, if only to keep the skin from collapsing.

It is that sense of frequently being confronted with absence, with sterility, that seems to most disconcert Steinbeck in his travels. On diner food: ‘Everything that can be captured and held down is sealed in clear plastic. The food is oven-fresh, spotless and tasteless.’ Is this is problem? He thinks so: ‘If this people has so atrophied its taste buds as to find tasteless food not only acceptable but desirable, what of the emotional life of the nation? Do they find their emotional fare so bland that it must be spiced with sex and sadism through the medium of the paperback? And if this is so, why are there no condiments save ketchup and mustard to enhance their foods?’

But Steinbeck never settles on a stolid opinion. He is always second-guessing himself, reminding himself on the food question that food in his boyhood was rarely good, that milk was riddled with deadly bacteria, and that people were frequently struck down and killed by ailments preventable with the implementation of basic hygiene. Surely, he chides himself this sterility, this sense of anonymity, is a price worth paying for a less brutish world? And that which Steinbeck criticises in America, he makes clear, he criticises in himself:

‘From start to finish I found no strangers. If I had, I might be able to report on them more objectively. But these are my people and this is my country. If I found matters to criticise and deplore, they were tendencies equally present in myself.‘

One might observe, for example, that his magnum opus The Grapes of Wrath depicts the violence of a family that is cleaved from the land of its roots by poverty, by mechanisation, by the greed of a few. But does he sentimentalise such abstractions as roots, he wonders?

‘Land is a tangible, and tangibles have a way of getting into a few hands. Thus it was that one man wanted ownership of land and at the same time wanted servitude because someone had to work it. Roots were in ownership of land... in this view we are a restless species with a very short history of roots, and those not widely distributed. Perhaps we have overrated roots as a psychic need. Maybe the greater the urge, the deeper and more ancient is the need, the will, the hunger to be somewhere else.’

This all sounds a bit worthy, but that wouldn’t give you the right impression at all. Steinbeck, as it turns out, is an extraordinarily funny writer. Consider him discoursing on the subject of turkeys:

‘To know them is not to admire them, for they are vain and hysterical. They gather in vulnerable groups and then panic at rumours. They are subject to all the sicknesses of other fowl, together with some they have invented. Turkeys seem to be manic-depressive types, gobbling with blushing wattles, spread tails and scraping wings in amorous bravado at one moment and huddled in craven cowardice the next.’

That acerbic wit is as good when directed towards his countrymen, say on the matter of Texan secession as it is cast over flightless birds:

‘We have heard them threaten to secede so often that I formed an enthusiastic organisation - The American Friends for Texas Secession. This stops the subject cold. They want to be able to secede but they don’t want anyone else to want them to.’

I do find it cheering in cases, such as in the lines above, that literature reaches out and drops into my lap the reassurance that people, particularly in their pettiness and foibles, don’t change so very much. We complain of our polarisation in modern political discourse, so it’s extraordinarily soothing to read Steinbeck’s depictions of conversations with acquaintances of a different political bent:

‘You talk like a Communist.’

‘Well, you sound suspiciously like Genghis Khan.’

And just as the laughable in humanity perseveres, so too does the repugnant. Of a group of women who showed up regularly at schools to harass African American children who were being bussed in to formerly segregated schools in the South, he applies a description that might as well fit the Alex Joneses, the Q-Anons, the Trumps:

‘Here was no principle good or bad, no direction. These blowzy women... hungered for attention. They wanted to be admired. They simpered in happy, almost innocent triumph when they were applauded. Theirs was the demented cruelty of egocentric children... they were crazy actors playing to a crazy audience.’

Travel writing doesn’t necessarily need to draw any significant conclusions on the nature of its subject matter; indeed, maybe it’s better if it doesn’t. ‘America is a country of contrasts and contradictions’ is as good a summation as Steinbeck can honestly make, and as good as summation too that a reader can make of Travels with Charley. With that humility that I mentioned above, the humility that makes me love Steinbeck rather than merely admire him, he ponders (to his patient audience of Charley the poodle): ‘I came out on this trip to try to learn something of America. Am I learning anything? If I am, I don’t know what it is.’

And the reader doesn’t really come away sure of what to think of this America, save that they’re happy to undertake any journey with Steinbeck as their companion. There ends my imperfect digestion of what might be a near-perfect book, and I can forgive myself for its limitations on the same basis that Steinbeck forgave himself for his limited depiction of America:

‘What I set down here is true until someone else passes that way and rearranges the world in his own style. In literary criticism the critic has no choice but to make over the victim of his attention into something the size and shape of himself.’