On cultural homework (2) and Catch (22)

Yesterday I sounded off on the idea of culture as homework, and today I feel the need to clarify that I am absolutely my own worst enemy in this regard. Over lockdown I set myself two silly and unwieldy goals: the first, to read all of Penguin’s 100 Greatest Novels, and the second, to watch the BFI’s Top 50 British Films.

Why do I do these things? Bloody-minded completionism, mostly, and a sense that if I achieve my goal I will be Cultured, and will somehow never feel obliged to read anything for the rest of my life.

The problem and the glory of this is that so many of my favourite books have come to me because of this self-imposed, masochistic cultural homework. I’ve been intermittently berating myself for about ten years for never having read, for example, The Master and Margarita or The Grapes of Wrath, and because of this project, I’ve read them. The beauty of reading books like these, even if you don’t enjoy them, is that a) you can have an informed opinion on why you think they’re shit and b) you never have to ask yourself again whether you ought to have read them. Oh, and you get to be smug. I trudged through The Brothers Karamazov about two years ago, and I’m still riding the wave of smugness.

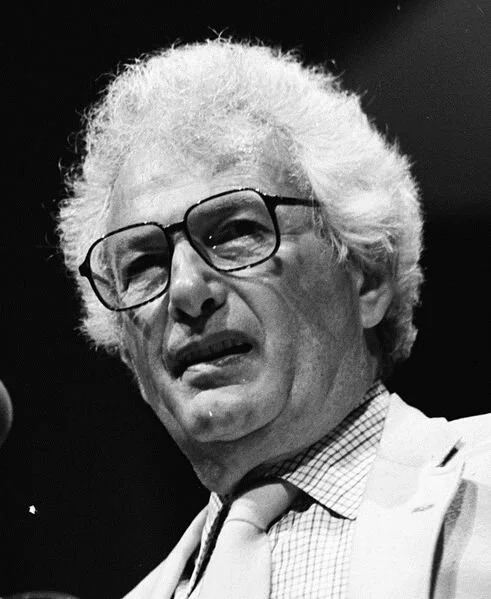

It was in this gloomy spirit that I approached Catch 22, and now, having finished it, I think Joseph Heller would have approved of my dreary approach to great works of art. And now, after fifteen years of guilt and about six aborted attempts, I can confirm that Catch 22 is indeed a great work of art*. It is basically Kafka’s The Trial, but with jokes. Really good ones.

One of the other useful things about working your way through The Canon (an unfashionable concept at the moment) is that you discover the genealogy of your favourite things. Catch 22 shares a sensibility with A Series of Unfortunate Events and The Thick Of It, which for my money are two of the greatest satires of the modern age. It has also helped me to understand such diverse phenomena in my own life as the Berlin bureaucratic machine, the handling of Covid-19, and the administration of Donald Trump.

I need to acknowledge, before I go any further, that I started reading Catch 22 in November and finished it today, so my memories of the first half are hazy (not the very beginning; as already discussed, I’ve read that about six times). I enjoyed it every time I picked it up to read it, but I was always warily waiting for the moment at which it stopped being funny and became merely interminable, which tends to happen with funny books. Think PG Wodehouse. Think Evelyn Waugh.

But this didn’t happen. What seemed at first to me like a directionless, baggy pastiche of a certain kind of bureaucracy proved itself to be a tightly-plotted and intently focused howl of rage and venom. Like all the best satire, Catch 22 has moral outrage at its heart. Think 1984 or Kafka - that despairing sense of being inside a closed system that can absorb any internal bleeding, any blows, any struggle, within the sheer fucked-upness of its logic. ‘Catch-22 says they have a right to do anything we can’t stop them from doing... They don’t have to show us Catch-22... The law says they don’t have to.’ ‘What law says they don’t have to?’ ‘Catch-22.’

And just as the best war films are always anti war films (Apocalypse Now, A Bridge on the River Kwai), Catch-22 comments best on war by not being about war at all, but about capitalism. This is embodied in the character of Milo, whose amoral endeavours to exploit market shortages to make a buck make him an excellent mess officer, a political figure of global significance, and an irredeemable human being.

Because I started the novel back in November I couldn’t tell you who most of the characters are, but I do know that at the heart of the book is Yossarian. Like Achilles, Yossarian refuses to fight (great art about war is always anti-war). Yossarian is a one-man paradox who is simultaneously forced, by his condition, to fight, and incapable, by his condition, of fighting. We find out what has happened to Yossarian, what he has seen. It is unbearable. Yet he has to bear it. The only way he can get out of it is to become like the people who put him there in the first place, in which case his position becomes untenable. Because to exist, in the world in which Yossarian exists, is untenable.

All this is to say that I loved Catch-22, and it changed my worldview, and it will live with me forever, and feed my love of books. A love that is paradoxically only maintained with a dreary and thoroughly un-aesthetic sense of bureaucratic, small-minded, listicle-obsessed completionism.

A love with a catch. Catch-22.

Nota Bene:

It would be remiss of me, as a feminist, to fail to point out that Heller’s depictions of women are appallingly and inexcusably misogynistic. This is neither a detraction to the novel nor an apology for it; it seems like Heller’s rage at humanity filtered through the misogyny of his time. There’s no reason to believe that he hated women more than he hated men, but that’s not to say that there isn’t a specific character to his depictions of women.

*It’s good to check for yourself on these matters. My investigations have informed me, for example, that One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest is total bilge.